Dear EKP Fans! We have a guest blogger for this installation in the person of Professor Lisa Lindsay, author of Wage Labor and Social Change in Southwestern Nigeria (Heinemann, 2003) among other books. Read below for the story of a man named Church and his mysterious placard that found its way into the pages of Ebony Magazine! Like, comment, share with your networks. And contribute your family history to the Ekopolitan Project. Future generations will thank you and so will we. EKPBose.

Thanks to the Ekopolitan Project for offering a space to consider a slice of the fascinating history of Lagos! I also appreciate the chance to share a photo and a mystery.

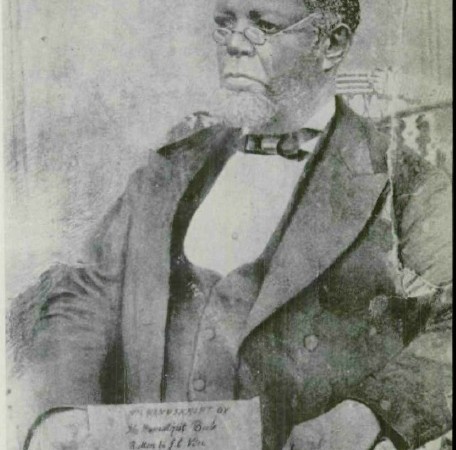

The photo is a portrait of James Churchwill Vaughan (1828-1893). It was published in Ebony magazine in 1975, but the original is held by one of his descendants in Lagos, Mr. Denji Vaughan.

“Church” Vaughan had a fascinating life. He was born in Camden, South Carolina to an African American former slave and his Afro-Native American wife. According to family legend, Vaughan’s father gathered his children around his deathbed and urged them to “return” to Africa. In 1852, Vaughan did, enrolling with the American Colonization Society as an emigrant to Liberia. What he saw in Liberia, however, gave him little incentive to stay. He accepted an offer of employment in Yorubaland with missionaries from the Southern Baptist Convention, and arrived in Ijaye to work as a builder in 1855. During the brutal Ibadan-Ijaye War, he was taken captive, escaped, took refuge in Abeokuta, and served as a sharpshooter. After missionaries were driven out of Abeokuta in 1867, he and other Christian refugees settled in Lagos, where he built a profitable hardware business and a well-known family. He also led a revolt against white missionaries, in the 1880s, helping to found the Ebenezer Baptist Church, the first independent church in West Africa. And he kept in touch with his relatives in America, who were embroiled in their own struggles for survival, prosperity, and dignity in post-Civil War South Carolina and elsewhere. Vaughan’s descendants included Dr. James C. Vaughan, one of the founders of the Nigerian Youth Movement, and Lady Kofo Ademola, promoter of women’s education and wife of Nigeria’s first Chief Justice. Politicians, diplomats, entrepreneurs, and educators, the Vaughans of modern Nigeria and the United States have maintained contact with one another over the past century. In fact, it was their trans-Atlantic family connection that was described and celebrated in the Ebony article on the Vaughans in 1975 (Era Bell Thompson, “The Vaughan Family: A Tale of Two Continents.”)

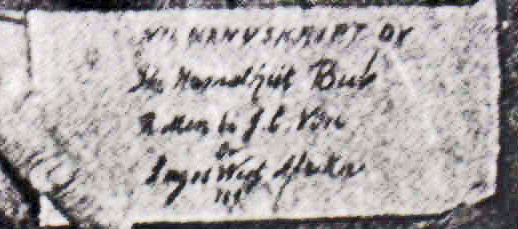

The mystery has to do with the sign that Vaughan is holding in the photograph. His portrait was taken in the 1880s, when Vaughan was a prosperous merchant. The first line seems to say “Viz [that is, “see”] manuscript by.” The second line is a name, perhaps beginning with “Mr.” The third line says, “Brother to J.C. Von,” followed in the fourth line with “of” and then “Lagos, West Africa.” Finally there is a date, 1880-something, with the last digit hard to read.

Why would Vaughan pose for a portrait holding such a placard? Whose manuscript was he recommending? Can anyone make out the name? It could not literally have been his brother, but who was so close as to be called that in a photographic print? I would be thrilled to know more, especially in time for the mid-2016 publication of my book on Vaughan (Atlantic Bonds: A Nineteenth Century Odyssey from America to Africa, forthcoming from University of North Carolina Press). Thank you for any suggestions!